Blackwater and botanical method aquariums are becoming more popular and for good reason. This naturalistic approach can more closely replicate tropical blackwater habitats where many fascinating and beautiful aquarium fish come from. Learn how to collect, store, and prepare botanicals such as oak, magnolia and bamboo leaves for your aquarium and the advantages and cautions of this fishkeeping method.

For most people, the arrival of the crisp fall air means it is time to get a pumpkin spice latte, enjoy the fall colors, and plan for the festivities in the months ahead. For blackwater fishkeepers, September and October are go-time for adult leaf walks to stock up for the year ahead in maintaining our botanical-style aquariums using what is available around us.

When I started keeping blackwater and botanical-focused aquariums, it wasn’t long before my fishkeeping hobby brought yet another hobby with it (fortunately, collecting leaves is much cheaper than aquarium fish photography!) Leaves I used to kick around absentmindedly and plan when to rake suddenly became more interesting. The trees in my neighborhood I’d barely paid attention to suddenly held new possibilities for my aquascapes. I found myself having flashbacks to being seven years old and picking up fall leaves for school projects. But now as a woman in her early 40s, I was examining the ground for the perfect leaves for my wild betta aquariums, coming home after every dog walk with pockets stuffed full of magnolia, oak, and other leaves I’d discovered in my neighborhood. I even started planning outings with my biologist friends to forage for alder cones.

Blackwater Fish Habitats

Most fishkeepers have heard of or used Indian almond (Catappa) leaves—the most commonly sold leaves for aquarium use. Indian almond leaves release plentiful tannins when immersed, which help acidify and tint the water closer to what many tropical freshwater species experience in their blackwater natural habitats, common in areas of the Amazon such as the Rio Negro, or the peat swamps of Southeast Asia.

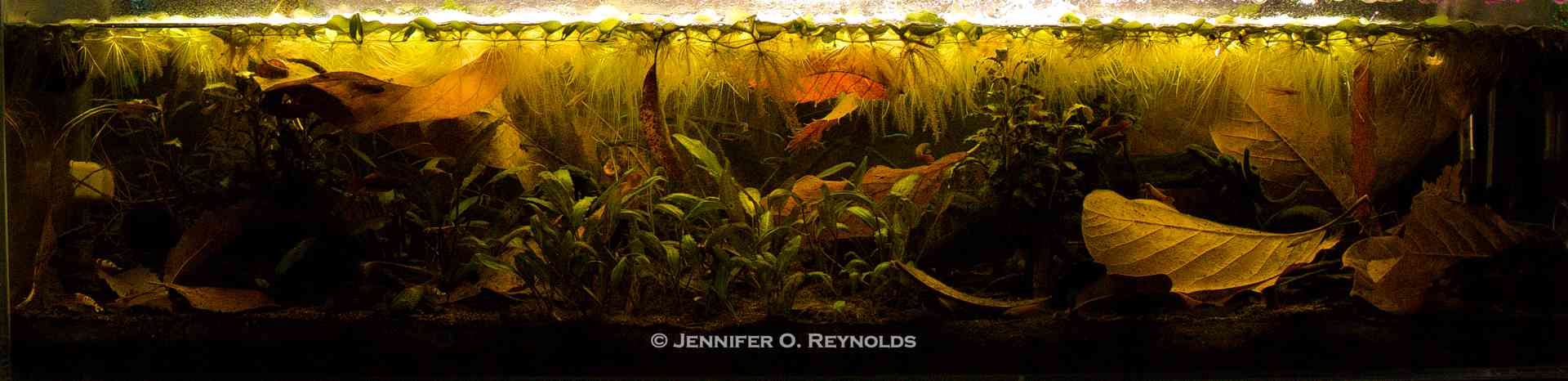

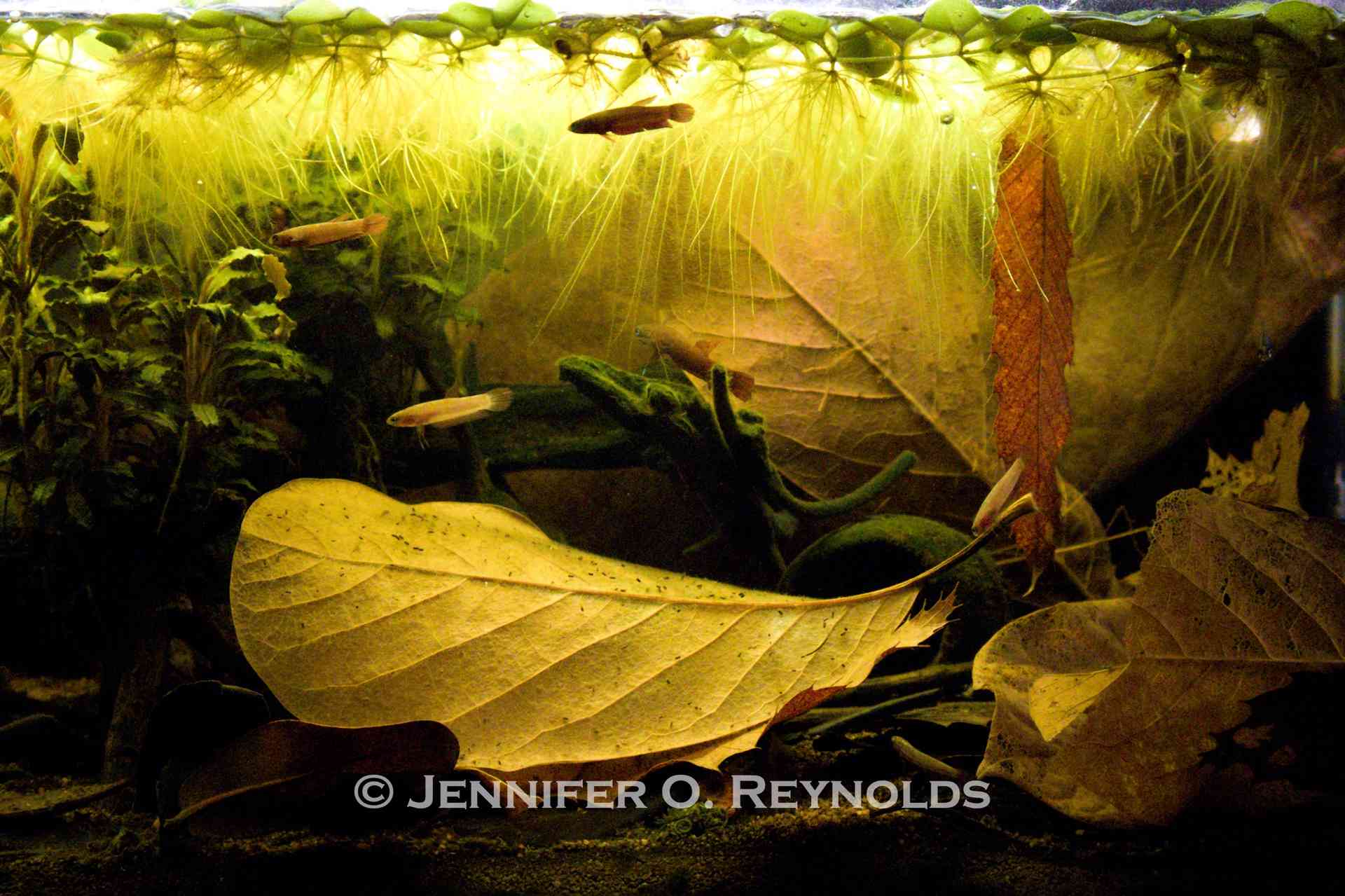

Many common aquarium species come from low pH blackwater in tropical areas around the world. These include cardinal tetras, dwarf cichlids like Apistogramma spp., many pencilfish, some Corydoradinae species, some rasboras and danios, licorice gouramis of the genus Parosphromenus, and some wild bettas I keep, such as Betta ‘api api’, B. albimarginata, and B. mandor, among others. Blackwater aquariums have a beautiful, warm glow that feels distinctly different from a typical clear-water tank, and the fish species that thrive in them are equally fascinating.

Collecting Leaves

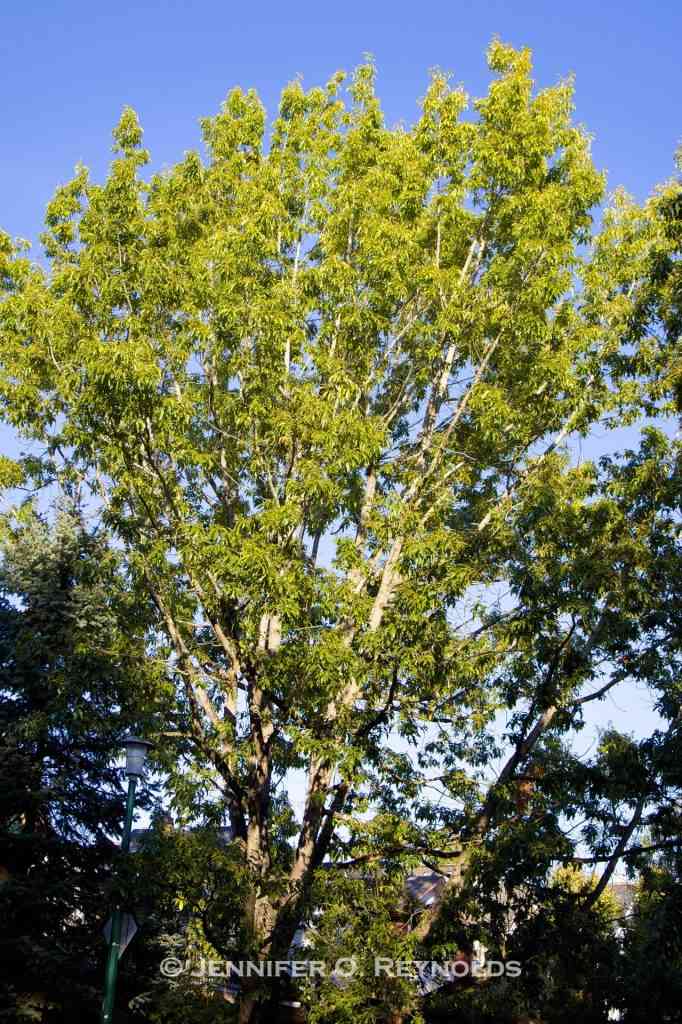

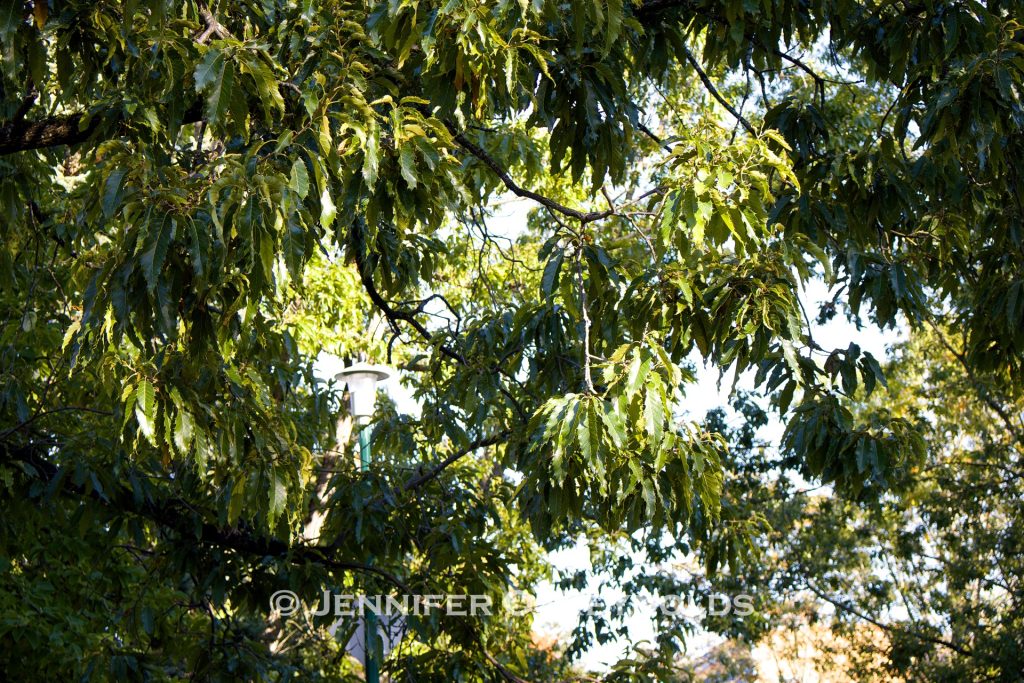

With many blackwater aquariums to maintain, relying solely on Indian almond leaves wasn’t practical. I wanted different shapes and sizes, so I looked for safe, tropical-looking leaves in my neighborhood. To my surprise, I learned that a nearby block was lined with a pretty oak tree I had never noticed before—a sawtooth oak.

These oaks are native to Eastern Asia, but have been introduced to North America. Here in Vancouver, they grow very well in our similarly temperate climate. Sawtooth oak leaves are quite beautiful and elongated, and since they last a long time in the aquarium environment, they make an excellent aquascaping component. Bamboo also grows abundantly in Vancouver, and I have collected dried bamboo leaves for my aquariums too.

Magnolia trees are common in my neighborhood. In the spring, I love to go for walks to admire their beautiful pink blossoms, but I was happy to have another reason to appreciate these trees in the fall. One of the most beautiful magnolias in my neighborhood has large, tropical-appearing leaves which are waxy, thick, and very easy to dry once I bring them home.

I have found that magnolia leaves do not last as long as oak leaves, but that shrimp such as crystal red shrimp love to feed on them, as do ramshorn snails. I credit dried magnolia leaves for the incredible crystal red shrimp population boom I experienced. The leaves decompose quickly, providing a continuous food source beyond the biofilm that usually grows on newly submerged botanicals.

Once the magnolia leaves have softened and are almost eaten, a beautiful skeleton of the leaf often remains, which I find aesthetically appealing in my aquariums. Bettas also adore hiding under these leaves and appreciate dried leaves added directly to the aquarium so that they are still floating, as a place to seek cover and relax underneath.

Alder cones are the locally-available botanical which in my experience are the richest source of tannins and are very effective in lowering the pH of water down to the levels some species prefer. For example, I keep my Betta ‘api api’ tank with a school of Sundadanio goblinus (which may actually be a different species) around pH 5.5. This is a good compromise which allows my crystal red shrimp to thrive and provides appropriate conditions for the blackwater bettas to spawn and rear young.

I prefer to avoid the use of peat to maintain my low pH, because harvesting of peat moss is not considered a sustainable practice and I am interested in preserving wetland environments, not further damaging them with my hobby. I also purchase exotic botanicals that aren’t available locally, like Savu pods (from the Brazilian Cariniana tree) and “Monkey pots”. Both come from trees related to the Brazil nut tree. I’ve found that my wild bettas enjoy hiding in them, and the small bubble-nest builders often use Savu pods specifically for nest building.

Drying and Storing Collected Botanicals

I’ve developed a simple system for collecting, drying, storing, and using my botanicals in my aquariums. There are many different ways to do this and many opinions on the necessity of boiling before use. I’ll explain my system, but you should gently experiment and determine what works best for you and how you’re maintaining your aquariums.

When I go for my leaf walks, I select leaves that have recently dropped and are not lying wet and rotting already. I pick leaves that are brown and not completely dried yet, but that do not show signs of leaf mold. I try to pick up large and small leaves so I have a variety available for my aquascaping use throughout the year.

When I bring the leaves home, I spray them and rub off any dirt using hot water. I then lay them on a towel on my floor (I have in-floor heating, which I think helps, but a space heater or any warm and dry indoor area should be sufficient to dry leaves), and I set a piece of Plaskolite lighting panel on top, which I keep around for aquarium purposes such as building dividers, temporarily lids, etc. Drying leaves flat makes them easier to pack for storage. However, curled leaves can create a more natural look in the aquarium, so you can choose whether flat, naturally curled shapes or a combo are best for the space you have available for storage.

After a few days, when the leaves are dry and crisp, I pack them into ziplock bags and add a large rechargeable silica gel desiccant package. This ensures that my leaves continue to dry and do not absorb moisture during storage, keeping them ready for use for years to come. I keep all my bags of leaves categorized in a small storage bin which is easy to pull out when doing maintenance so I can pick which new leaves I want to add.

Preparing Botanicals: To Boil or Not to Boil?

When I first set up a new botanical-style aquarium, I will often boil a number of leaves for this initial setup. This helps them sink faster and turbo-charges the release of the humic and fulvic acids within, which can help lower the water pH and provide a tint.

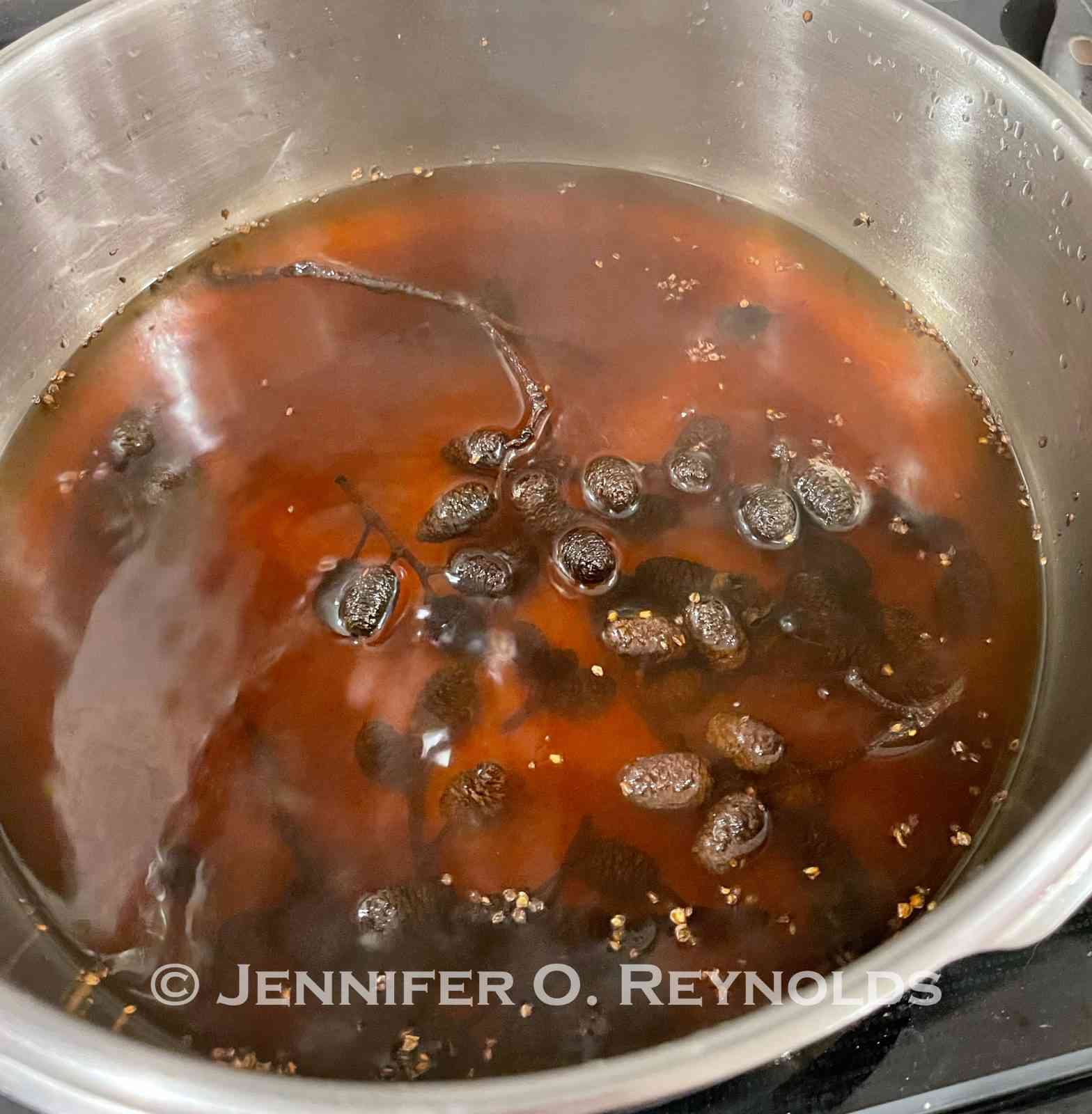

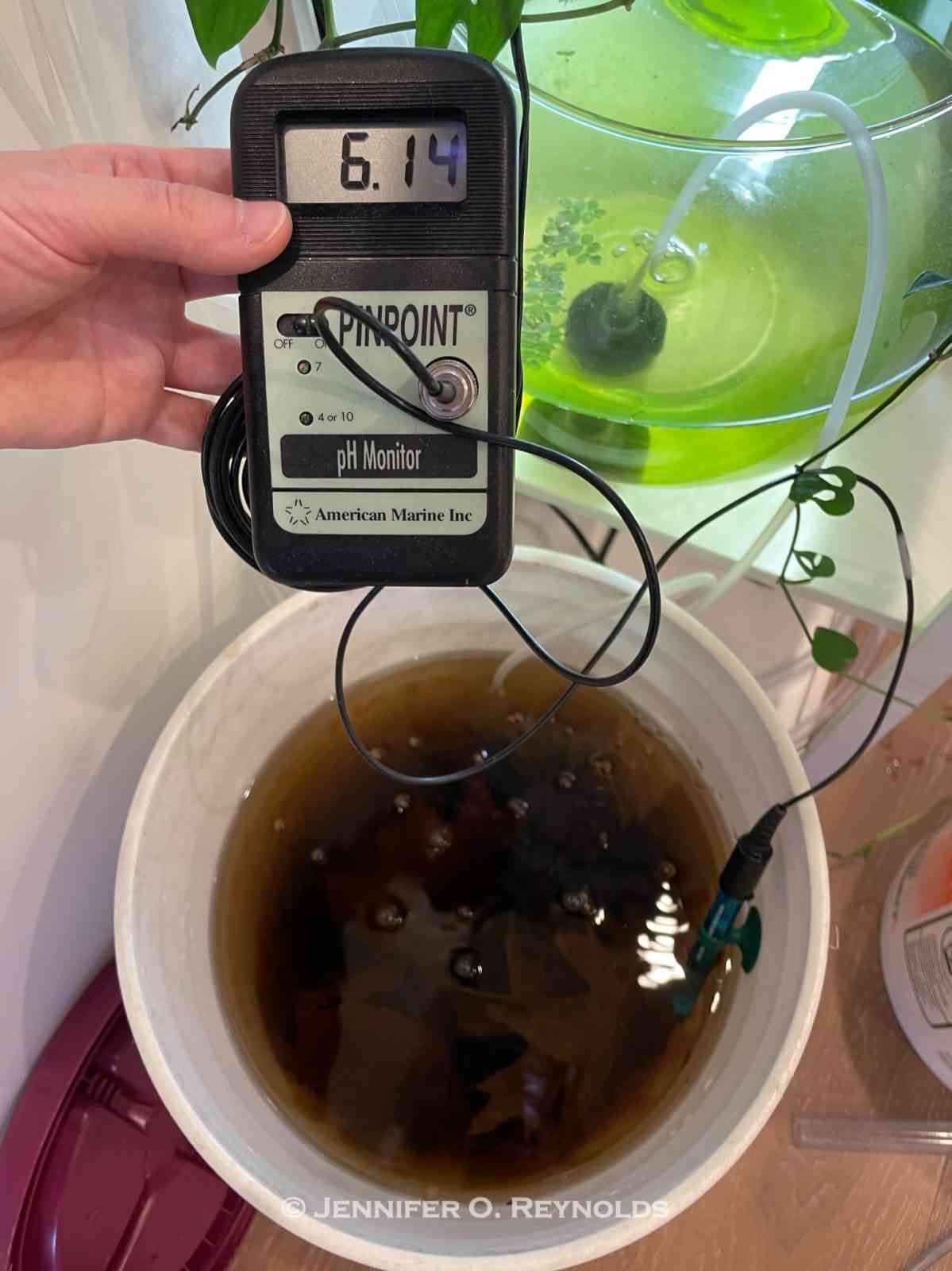

I also boil alder cones and use only the darkly tinted water to add tannins to my aquariums as needed to maintain the blackwater appearance and/or further acidify them, even if I do not add all the cones to the aquarium. I often use the leftover cones to continue tinting and acidifying my bucket of top-up water which I keep prepared for use in water changes.

The acidic concentrate resulting from a boiling session can be cooled and added to the aquarium to lower pH as needed. Tannins have a tendency to be consumed in the aquarium. If you’re trying to maintain a tint in your water, do not use carbon in your filter and be aware that many planted aquarium substrates will have a tendency to pull these substances out of the water column. My tanks where tannins last the longest are tanks with sponge filters and inert sand: no floss, carbon, or planted-aquarium substrate such as Stratum, Aquasoil, etc. You can still use these—and I do, in some setups—but be prepared to add more tannins regularly if you want to maintain a blackwater appearance.

Boiling the leaves, seed pods, and cones also helps with precise placement in the tank during the initial setup or tune-ups, as it water-logs them, allowing them to sink. A botanical method aquarium is constantly evolving. How your tank looked three months ago will differ from how it looks three months from now—or even a year later. This is a different experience from many other aquarium setups which are more static in their appearance.

Since I am careful in my initial selection of leaves and rinse them before I dry them, I am not concerned about adding my dried leaves directly to my aquarium. I often do this after a water change and as an ongoing part of maintenance. I have had no issues adding dried leaves without pre-boiling; all the fish in these tanks are healthy, vibrant, and regularly spawning.

Whether to boil or not is your choice. When purchasing botanicals from an unknown source, boiling can add an extra layer of safety, and you should follow any instructions provided by your botanical supplier. At the very least, a rinse and scrub with hot water could remove unwanted debris ahead of use. In Vancouver, leaves can become coated with particulates from city smog and forest fire smoke, so I clean my leaves before drying and storage. It is unusual for trees in my area to be sprayed with pesticides, so I am not concerned about this, but do pay attention to this in your local area for caution, if not using trees from your own backyard (if you are lucky enough to have one.)

What to Expect When Adding Botanicals to Your Tank

Adding too many botanicals to an aquarium at once could result in a bacterial bloom or population boom of (harmless) detritus worms or ostracods. Be judicious with the amount you add at any one time, as the leaves are fuel for other organisms in the aquarium system, for better or worse. You will see slimy biofilm on many botanical surfaces in the days after immersion. This is just part of using botanicals and is usually harmless to tank inhabitants, although I have had bettas pick up bits of water mold on their skin if they are exposed to too much of this in a new aquarium. I like to keep ramshorn snails and Amano shrimp—both of which eat biofilm—in most of my tanks to help combat too much of it from taking hold, as I personally don’t love the appearance of it, despite knowing it is natural.

Another caution is that some wild betta keepers have noted that wild bettas and licorice gouramis are very susceptible to the parasitic dinoflagellate commonly known as Velvet (Piscinoodinium sp.) This can be a deadly disease and has impacted the collections and breeding programs of many wild labyrinth fish keepers. Luckily, I have not yet encountered issues with this organism in my collection, but I have had well-respected aquarist colleagues tell me that the use of dried leaves can increase the risk for this disease in their experiences. I chose to try to prevent the introduction of this into my systems by carefully quarantining all my new arrivals using UV filters.

An assortment of leaves ranging from newly dried and floating ones to dark leaves that have been decomposing in your aquarium for months creates a realistic and natural habitat for blackwater fish. As noted, the leaves provide fuel for microorganisms, but this can be beneficial if raising very small fry and allowing them to grow in the same tank as the adults. Betta fry I have allowed to remain in the tank environment rather than pulling out to separate fry-rearing tanks have consistently fared better and grown faster, perhaps because they can constantly graze on microorganisms throughout the day rather than relying on a few influxes of fry food from the aquarist.

Fish Behavior and Botanicals

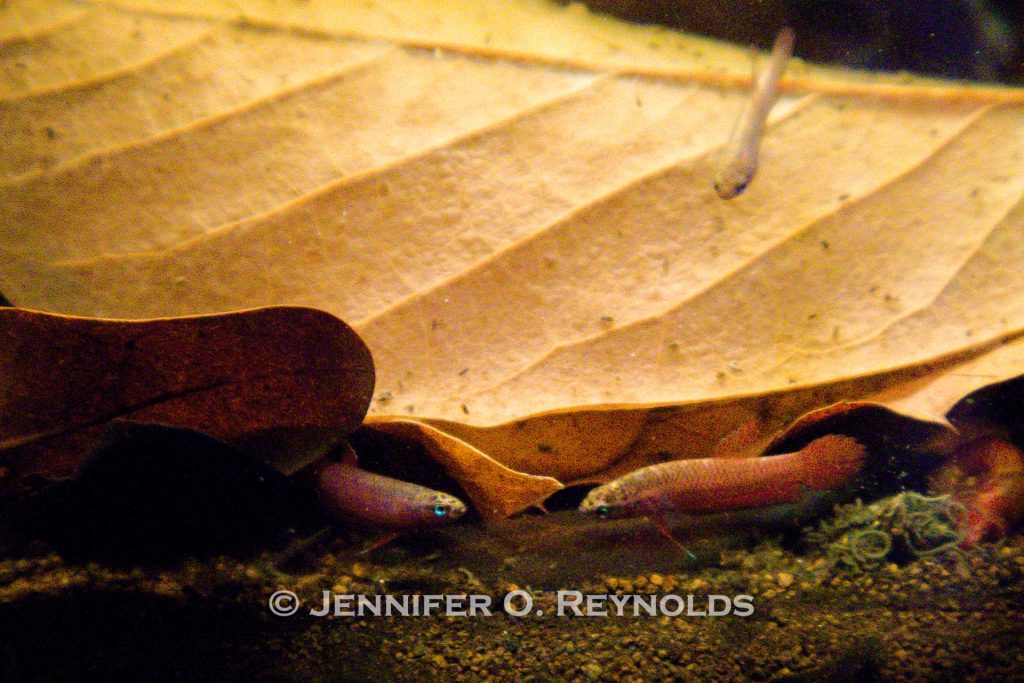

I like to use these leaves to provide visual barriers for my wild betta specimens, in addition to aquatic plants—all of which help mitigate their aggressive tendencies. Smaller betta species such as the Betta sp. ‘api api’ display their most natural behavior when in a tank full of leaf litter. They slither through it and interact constantly with the labyrinth of nooks and crannies the leaves create.

I have also found that cory catfish enjoy foraging around and under leaves; our fish veterinarian Dr. Hickey uses dried leaves such as almond leaves and alder cones to acidify her water and provide foraging areas for her cory cats. A funny quirk of the Betta albimarginata I have observed is that they just adore hanging under a leaf placed horizontally in the middle of the water column. Time and time again any leaves I can place in this position will soon be providing shelter for a happy little betta who feels secure and protected from the genetically programmed fear of predation from the skies. Fry of this species seem even more reliant on the protection of leaves, and I consistently find them curled up underneath a piece of leaf litter when a new batch of fry has been released from the male’s mouth.

Take a Leafy Adventure

What leaves can you find in your neighborhood that you could use in your aquarium? Although I prefer the more exotic appearance of the sawtooth oak and magnolia available in my neighborhood, red oak or pin oak are common throughout North America and can be a great choice for providing interesting habitat and a source of tannins to your aquarium. If you’ve never used leaves in your aquarium before but want to try, consider getting your feet wet first by using some Indian almond leaves, especially if you keep bettas or other soft water fish.

Including botanicals in my aquarium environments has transformed the way I keep fish, and the fish are certainly better off for it. A great bonus has been getting to know and enjoy the trees in my neighborhood through new eyes, and the fun conversations I’ve had with neighbors who are curious why I’m helping them with their leaf cleanup. Enjoy your leaf walks!