Jennifer O. Reynolds, M.A. & Nora Hickey, D.V.M.

Jen and Nora discuss how to effectively use aquarium salt to treat common problems in freshwater fish including Ich, Epistylis, open wounds, and nitrite poisoning. They provide recommendations for proper aquarium salt dosage using accessible products that can be helpful for bettas and other freshwater species.

Jen: Nora, I think it’s time we cover one of the most pragmatic and easily accessible tonics for freshwater fish: aquarium salt. Salt is inexpensive, easy to keep around, relatively gentle on fish and has so many uses. Let’s chat through the different scenarios where fishkeepers can use salt to help their fish, and how to appropriately dose. As a fish veterinarian, what is the first use that comes to mind for you when thinking about dosing salt in a freshwater aquarium?

Nora: I think relieving osmoregulatory effort is one of the most valuable things salt does for fish. It’s not easy being a freshwater fish, since the water outside of them is always being drawn into their bodies because of diffusion. Fish put a lot of energy into maintaining the right ionic balance in their bodies (read more about that process here)! So when a fish is having a hard time, whether it is an infectious disease, new introduction, or just “not doing right,” salt is such an easy way to help them.

Jen: That is particularly the case if they have a wound or some interruption to their slime coat isn’t it? Having slightly saltier water in the aquarium reduces the amount of salt and other ions that the fish is losing and fighting to maintain for its physiological functions. Low level salinity like this can also prevent some common problems that occur if a fish has a wound. Can you tell us more about this?

Nora: Salt does two things in this case. First, it relieves osmotic effort, which is the energy the fish is spending maintaining proper levels of different ions. And second, it can help prevent some opportunistic infections with bacteria, water molds, and parasites.

Salt, even at low levels, can help inhibit the growth of these infectious agents. So if you ever have a suspicion of some kind of pathogen causing problems for your fish, salt is probably not going to hurt and can often be quite helpful!

Jen, can you tell us about your experience treating Epistylis with salt when you worked at the Aquarium?

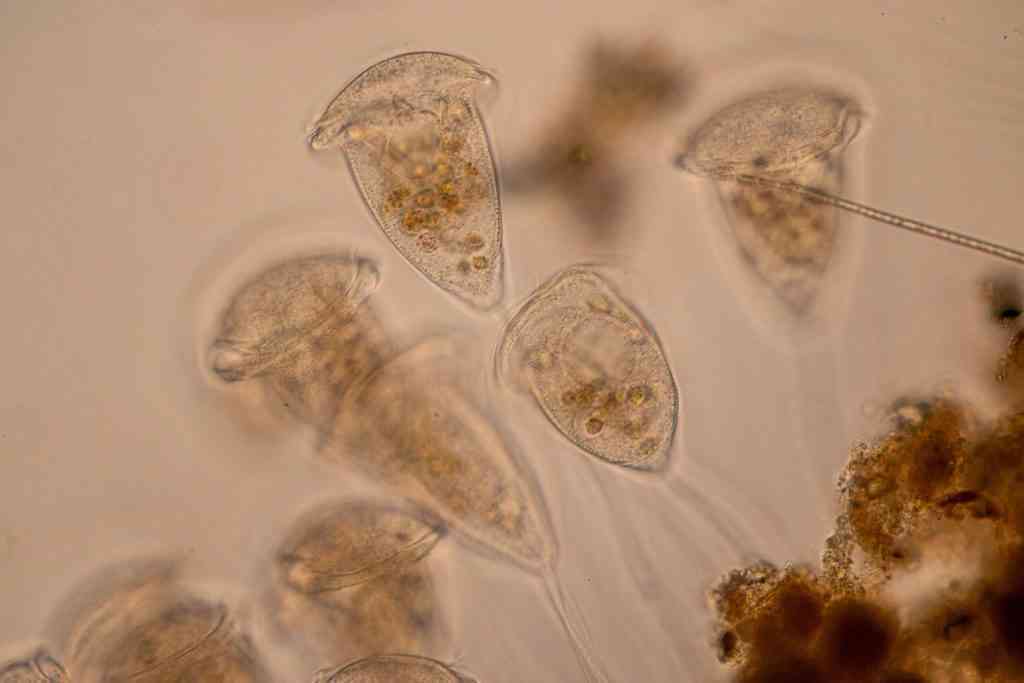

Jen: Salt was the number one treatment I applied to our extensive freshwater fish collection during my many years at the Vancouver Aquarium. With a shared water system and many species living together, occasional wounds would inevitably occur and become infected, typically with water mold, which, if left untreated, could progress and become a real problem for the fish. We also had species that for one reason or another seemed very susceptible to Epistylis. In our collection Epistylis most often showed up as cottony white tufts on the mouths of some fish and became easy for me to visually distinguish from a more problematic issue such as ich, since we were always able to verify the parasite in question with skin scrapes.

Salt worked amazingly well as an Epistylis treatment. We used 3 ppt as a prolonged bath (1-3 weeks most often) on many species. I never lost a fish from dosing salt this way—even some of the more seemingly sensitive ones such as knifefishes or catfishes.

We would sometimes apply low level salinity (2-3 ppt) to our entire system when a systemic issue would crop up. But more commonly we would remove a fish with issues to an isolation tank to do this treatment. The high level of organics in a large shared water system was part of what contributed to the issues. Interestingly, some species were highly susceptible to Epistylis, for example the Congo tetras I mentioned earlier. I was therefore never able to display a school of them in our main water system. Epistylis never killed them but caused unsightly chronic growths on their mouths.

It is also possible to treat ich with salt. I think where many fishkeepers run into trouble is that they are scared to dose as much salt as is needed, and they don’t understand the full life cycle of that parasite. Oftentimes, ich will look worse before it gets better, because a salt treatment does not kill the visible manifestation of the infection on the fish; rather, you’re targeting a vulnerable part of the parasite’s life cycle and have to wait for that to work its way through. This is why early detection and action is important, and keeping salt on hand is so useful for freshwater aquarists.

Nora: Salt is super effective against Epistylis. As we talked about in our Ich versus Epistylis conversation, Epistylis is a sessile ciliate parasite that is opportunistic. Something else has to be off in the fish’s environment, such as high levels of organic debris or poor water quality, for Epistylis to cause a problem. But for situations when Epistylis is causing a problem, a salt dip or a prolonged salt bath will effectively treat this parasite.

Because there are often other problems in the environment that cause Epistylis infestations, things like poor water quality or high levels of organic debris also need to be fixed to effectively treat this problem. Treating with salt is the first, but not the only step to dealing with Epistylis.

Your observation that many hobbyists struggle to treat Ich with salt is spot on. Unlike Epistylis, which can be treated effectively by a salt dip (a dip is a short-duration treatment where the fish is immersed in a salt solution for seconds to minutes), Ich is more resistant to salt treatment at certain life stages. The trophont life stage, which is the Ich that you see as white spots on an infected fish’s skin, is buried underneath the surface of the skin and protected from the external environment. So salt dips do not effectively treat Ich during this life stage.

To effectively treat Ich with salt, prolonged immersion in a salt bath (a bath is a long duration treatment where the fish is immersed in a salt solution for days to weeks) is needed for effective treatment. The exact duration of treatment depends on the water temperature, but this would be around one week for a tropical aquarium. People often see recommendations to increase the water temperature for Ich treatment, and it is because increased water temperature accelerates the parasite’s life cycle into life stages that are vulnerable to salt.

Jen: Right, so if you add the salt to the aquarium and the Ich seems to be getting worse, that does not necessarily mean the treatment isn’t working. It’s just that it is not treating the white spots on the fish, yet, as those really just have to go through the process of rupturing and leaving the fish’s body. There is actually nothing that can be done about those. The plan with using salt to treat Ich is to interrupt and kill the vulnerable next phases of the parasite (tomonts and theronts) which are in the water and vulnerable to the salt treatment. That’s why it is so important to observe your fish and have a treatment plan ready to go at the first signs of Ich. If you can interrupt that life cycle earlier in its progression, your fish have a better chance of surviving the assault. I really encourage hobbyists to consider dosing salt at the first sign of something amiss, because it is very hard to cause problems with salt when dosed correctly.

Nora: One thing I do wonder about though is how much salt different plants can tolerate during this type of long-term salt treatment.

Jen: While it is true that aquatic plants can be damaged by salt, I’ve managed to use prolonged salt baths (1-3 ppt) without major issues on plants. Higher levels can damage plants, so I would not recommend higher concentration salt treatments (over 3 ppt for example) with plants involved. In the past, I’ve had to treat large aquarium systems containing knifefish, pictus catfish, electric eels, and other fish often considered sensitive to salt. While the electric fish found the increased conductivity due to the salt difficult and did not eat or swim well during the treatment, they all survived.

Nora: That’s good to know that most aquatic plants can tolerate the dosage of salt that is effective against many parasites. In general, 1-3 ppt of salt is not only effective against many parasites but also provides some relief of osmotic stress for sick fish. Even if salt isn’t an effective treatment for whatever infectious agent the fish have, it can at least make it easier for them to maintain their physiologic functions. Jen, I know that you were commenting the other day about how sometimes it’s surprising how much salt that actually looks like when you measure it out to add it to your aquarium!

Jen: Yeah, you know, even after over 20 years of using salt to treat various fish ailments, it still sometimes shocks me a bit when I see the physical volume of salt I am about to add to my aquarium to get to the desired dose. I feel confident with it because I have a lot of experience doing this, but I think that many people may be underdosing salt in their aquariums for this reason and might not be getting to effective levels for treatment.

I first calculate my water volume and the desired treatment dose, then I use a kitchen scale to weigh out the required salt dose into a jug. I dissolve the salt slowly with water from the aquarium and start gently pouring the brine throughout the aquarium. You can add it bit-by-bit over several hours if you wish, but I have found that fish adapt well to the addition of these low levels of salinity and I haven’t had issues with adding it over 10-20 minutes. I think it is important to avoid adding salt crystals directly to the aquarium, so ensure what you are adding is fully dissolved first.

While several aquarium supply companies sell salt that can be used for dosing freshwater aquariums, it is also possible to buy the salt you need at the grocery store. Pickling salt is a great option. Typically, pickling salt is larger sized crystals than table salt and has no additives.

Table salt is not a good choice as it commonly contains iodine added for human health which could be problematic for fish. There are also some anti-caking agents such as yellow prussiate of soda present in some salt types which are best avoided for aquariums, especially if using a UV sterilizer as this light exposure can make those components more toxic. As far as aquarium salt options go, don’t use salt for marine aquariums as it has other substances to create marine water conditions that will affect pH, KH, GH etc.

Nora: Many aquarium salt brands will recommend dosages in tablespoons per gallon; for example, 1 tablespoon per 5 gallons is roughly 1 ppt salt. Kitchen scales are cheap and easy to acquire from your local grocery store or online, and it is more accurate and precise dosing if you use one of these.

Another problem that this dosage of salt in your aquarium will treat is nitrite toxicity. Because nitrites are taken up through the gills using the same mechanism as chloride uptake, salt competitively inhibits nitrite uptake through the gills and effectively treats nitrite toxicity at the right dosage. A dosage of 1 ppt salt is likely to be more than enough to treat high nitrites in any home aquarium.

Jen: Great point. I’ve used salt to treat nitrite poisoning I had in an aquarium after installing a new canister filter on it that wasn’t populated with enough nitrifying bacteria to cope with the fish population in the tank. It worked perfectly. Fish stopped dying and gasping at the surface. Salt dosing is such an elegant solution to such a potentially deadly problem. I think that nitrite toxicity is not well understood by many hobbyists, because it’s hard to believe how toxic it is even at very low levels.

Nora: Nitrite kills! The reason your fish were gasping was because it causes methemoglobinemia—they literally have no oxygen being delivered to their cells! And it’s kind of mind-boggling that something as simple as salt can fix such a lethal health condition as nitrite toxicity, as well as very common problems like ectoparasites. I’m leaving this conversation thinking that if something seems wrong in one of my aquariums, I will start with salt!

Jen: I agree. Salt can treat many of the common issues that crop up in our aquariums, including wounds, osmoregulatory stress, water mold (“fungus”), Ich, Epistylis, and nitrite toxicity, to start. Using a low level salt immersion of between 1-3 ppt is a great starting point. From there, I recommend observing your fish and the progression (or hopefully, resolution!) of the issue to determine if you’ll need to seek any other intervention or if you’re dealing with something that is salt-treatable. Salt is an inexpensive and gentle intervention with the potential to help your fish out significantly when dosed at the right levels. I hope our chat today will help fishkeepers feel more confident in dosing salt in their aquariums!

Relevant Articles:

“Do Fish and Sharks Drink Water?,” Nora Hickey, D.V.M., for Dr. Universe

Reputable Resources:

Noga EJ. Fish Disease : Diagnosis and Treatment. Second edition. Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

Nitrite in Fish Ponds, Southern Regional Aquaculture Center Extension Publication