Jen and Nora confer on mycobacteriosis (often called fish tuberculosis) in aquarium fish and offer recommendations for aquarists who are concerned about or dealing with these pervasive bacteria.

Jen: This week let’s talk about mycobacteriosis, Nora. Aquarists call it “myco,” and it’s also known as piscine tuberculosis, or “fish tb” which does sound scary. It seems that any aquarist who has worked professionally in the field or who has a years-long or multiple-tank type of hobby has encountered it in one way or another. It was definitely an ongoing issue in the fish collection I cared for at my job. Let’s start by explaining what myco is and how it gets in our tanks.

Nora: “Myco” refers to a group of many different bacterial species, specifically the Mycobacterium genus, and these bacteria are everywhere. If you have a fish tank, you probably also have mycobacteria. Mycobacteriosis is what we call the disease that a mycobacterial infection causes.

These bacteria live in biofilms in the aquatic environment–they are in your tank substrate, the filter, on the aquarium glass, plants, etc. Certain fish, including syngnathids such as seahorses, are notorious for their susceptibility to mycobacterial infections, but these are bacteria that can affect pretty much every species of ornamental fish.

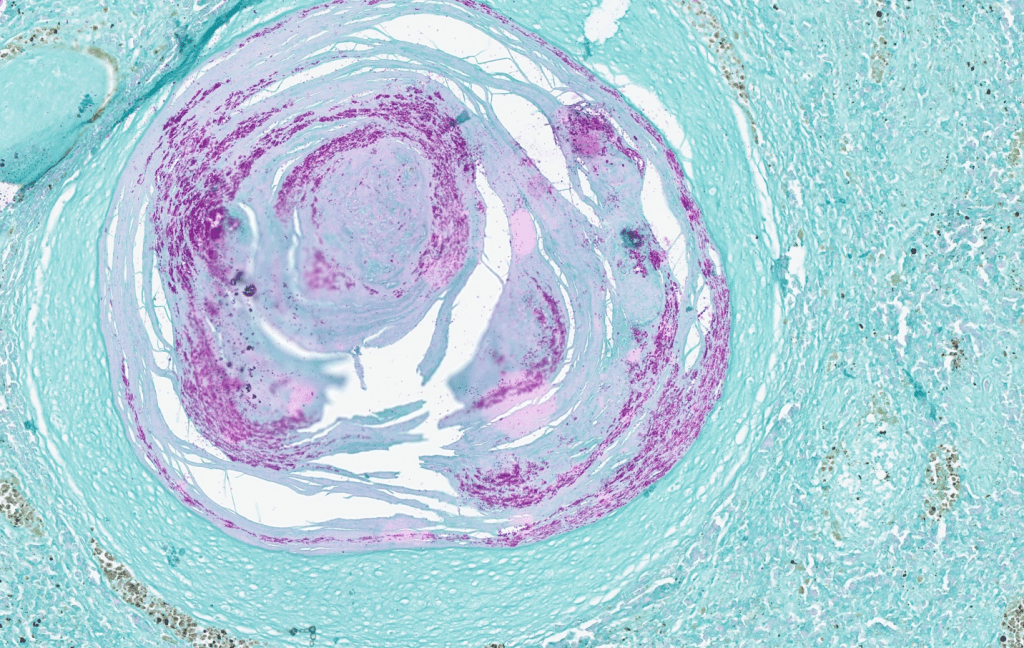

When it infects fish, it causes a type of immune response called granulomatous inflammation. Granulomas are concentrated areas of white blood cells in the fish’s organs. Granulomas are an aspect of mycobacteriosis important to understanding why this bacteria is so pervasive in the aquarium hobby and so challenging to manage.

Jen: Why are granulomas important to understanding myco? What is it about them that makes the disease so difficult to manage?

Nora: Some bacteria kill quickly by releasing toxins that spread throughout the fish’s body or quickly replicating in and destroying critical organs. Mycobacterial infections are not like this; granulomas are a slower form of inflammation and a sign of a more chronic disease process. A fish can be infected by mycobacteria for a long time before showing signs of disease. A fish could even be infected with mycobacteria and have some granulomas, but die from something else. The slow progression of mycobacterial infections can make it hard to notice until a fish has significant disease and has been shedding mycobacteria and infecting other fish in its environment for some time.

Another challenge of diseases with granulomatous inflammation, like mycobacteriosis, is that they are difficult to treat because many antibiotics do not penetrate into the bacteria inside of the granuloma. So while there are many bacterial diseases of fish that can be treated with antibiotics, sadly mycobacteriosis is not one of them.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Jen, don’t you have a friend who recently had a mycobacterial outbreak in her home aquarium and was able to successfully manage it?

Jen: Indeed I do. That was a tricky and very interesting situation especially since she had only started keeping aquariums a year prior to that. I’ve unfortunately had a lot of experience with mycobacteriosis at the Aquarium, where it was a chronic issue that did affect the fish but was only occasionally directly implicated in mortalities. Mortalities from it were primarily in susceptible species we had, like rainbowfish. I do believe that the chronic exposure to mycobacterium in our shared water system may have affected all the fish in some ways, whether it was spawning less, growing more slowly, or not maintaining body weight well. The types of stressors fish in a public aquarium are routinely exposed to might also make them more susceptible.

Despite that experience, when my friend had sudden fish deaths that at one point appeared as ulcers and white patches on the body of the fish, myco just didn’t come to mind for me in a 10-gallon planted platy tank, you know? Because these were home aquariums we couldn’t properly diagnose anything either, at least not until we got you involved.

Nora: Myco wasn’t my first thought, either, when you told me about what was going on in your friend’s tank. But it’s one of those diseases that can present in a lot of different ways. The chronic mycobacteriosis you dealt with at the Aquarium is probably the most common presentation of this disease—occasional deaths of the more elderly fish in the population. These bacteria can infect a fish for years without causing significant problems, except for that fish shedding bacteria and infecting all of the other fish it is living with. If one fish in a tank has myco, they are all probably infected.

In your friend’s case, it was a more recently established aquarium, and the platys had skin lesions that made me more suspicious of columnaris disease. However, as we discussed in our conversation about diseases that cause white spots on fish’s skin, most fish diseases cannot be diagnosed just by a visual examination of the fish. Your friend was able to submit some fish to our veterinary diagnostic laboratory, and a veterinary pathologist at the laboratory diagnosed them with mycobacteriosis.

Jen: When you came back with that diagnosis I was so surprised at first! But then I felt like it should have been obvious because some of the fish had a general failure to thrive and were just too skinny despite ample food present.

At that point there were two main issues we had to tackle. The first was educating my friend on how to protect herself from possible mycobacteria infection, since it is zoonotic—meaning it can infect humans. Many of my professional colleagues have been infected. Somehow I managed to dodge it over all those years by being very careful not to expose any wounds on my hands or body to the aquarium water, or maybe just by luck.

Then the second issue was how to advise her to manage it in her tank, since we know it is not something that can be eradicated, but also that it shouldn’t be killing fish rapidly. I was super disappointed that she was having to tangle with this nasty issue so soon after entering the hobby.

Nora: Yes, it’s important to address the fact that mycobacteria that infect fish can infect humans, but to remember that fish mycobacteria are not good at infecting humans. This disease is treatable and uncommon, so worry about it should not prevent anyone from enjoying the aquarium hobby. But, definitely talk to your human physician if you have any concerns. The disease that fish mycobacteria can cause in people is colloquially referred to as “fish handler’s disease,” which presents as granulomas on the fingers. Not getting aquarium water into open wounds will prevent mycobacteria in aquarium water from infecting you. And like many infections, mycobacteria are more likely to be a problem for people who are immunocompromised.

Jen: If you do have any sort of unusual lesions on your hands or arms, do mention to your doctor that you have aquariums, because they might otherwise not think about this possibility. Even though it is rare as you said Nora, I do have a number of aquarist friends who’ve been infected and had to undergo treatment, so it is always good practice to avoid aquarium water in any wound. Long rubber arm gloves can be used when you have a wound you need to protect. We definitely don’t want anyone to be scared off of this amazing hobby due to this bacteria.

Nora: PSA to our readers: Be careful of some Google results for “long rubber arm gloves”…

Jen: Oh dear! I’ll spare them this surprise by linking to the ones I’ve used…!

Nora: But while we can protect ourselves with simple measures like gloves, it is harder to protect the fish in our aquariums from this disease. Mycobacteriosis is a common problem in home aquariums, and there is no treatment for fish that become ill. And because this bacteria is so ubiquitous and slow to cause disease, it is not something you can keep out of a tank with good quarantine practices like we discussed in an earlier conversation.

However, you came up with a very clever idea that significantly improved the situation in your friend’s tank—so tell us about it!

Jen: It seems like all my clever ideas lately are related to the same piece of equipment! Before we get to that, we had to think through why her tank ended up having so much myco that the fish actually got sick from it, which as you pointed out, is certainly not always the case. Some contributing factors I noted and helped my friend correct were a slightly too-warm tank temperature which could amplify the growth of bacteria, accumulated organic detritus from driftwood and plants and suboptimal water quality for the platys, in conjunction with the general susceptibility of livebearers like platys to this bacteria.

The goal ultimately was not to eradicate the mycobacterium, since that is a fool’s errand, but to significantly reduce the amount of it in circulation so the fish’s immune systems could better handle it, and to correct some of the underlying contributing factors to support the fish’s immune systems. We had to accept that she’d have mycobacteria present, as most aquariums likely do, but make changes that could prevent her fish from succumbing to mycobacteriosis.

Once again, the fabulous mini UV filter came to the rescue. The idea is that by destroying some of the myco in circulation it can help keep the amounts in check relative to other common bacteria and give the fish a much better chance to fight it off. In conjunction with lowering the temperature slightly and improving water quality, culling the most severely affected fish so that they wouldn’t keep shedding large amounts of bacteria, and increased removal of detritus, the UV filter did do the trick. Since then, her fish seem healthy, are breeding, and she doesn’t lose any more than one might expect in an average aquarium. It made a huge difference. My opinion is that managing myco in an aquarium requires a multi-faceted approach. I’m not here to suggest that a UV filter is a cure-all.

Nora: But it’s something! As you previously mentioned, it can be incredibly disheartening and overwhelming when you face a mycobacteria outbreak in your aquarium. The prognosis for an individual fish that has mycobacteriosis is grave. That fish will inevitably die, and when this happens there can be a strong urge to either give up or start over. However, mycobacteria are pervasive across the aquarium hobby, so it’s pretty much impossible for the average hobbyist to keep mycobacteria out of their tanks. But there are some things you can do to make your tank environment unpleasant for mycobacteria and your fish robust enough to fight it off!

Mycobacteria are not something that quarantine is effective in keeping out, so be discriminating in selecting new fish for your aquarium. Don’t buy sick fish. Don’t buy healthy-appearing fish that are in tanks with sick fish. Maybe don’t even buy fish from a store that has sick fish in any tanks (because many of these tanks are on the same system). And don’t buy too many fish! Not overstocking your aquarium is another important way to keep fish healthy and prevent mycobacteriosis as well as other diseases, although exactly how many fish to keep in an aquarium is a conversation for another time.

Maintaining excellent hygiene including performing regular water changes, keeping filter material clean, and the use of a UV sterilizer will help keep the bacterial population low enough not to overwhelm your fish’s immune systems. If you have sick fish, they should be immediately removed to a separate tank for proper treatment and so that they do not shed pathogens that can infect the rest of the fish.

Jen: Nora, I think you and I agree that overall, most healthy fish can handle some exposure to mycobacterium. If they couldn’t, the tropical fish hobby would be entirely hobbled. It’s when the amount of bacteria is overwhelming, the species is particularly susceptible, or the underlying immune response of the fish is suboptimal that we start to see it present as a disease with ulcers, wasting, mortalities, etc. So we’ve got to think about how to best support the health of our fish. For each species, this is going to look different. Definitely, good husbandry practices including filtration and water changes are a basic piece. We want our fish to be thriving, not just surviving, and there are many factors that influence this.

Optimal water quality for the species is important, as is good nutrition. Livebearers kept in acidic, mineral poor water are unlikely to be in optimal health and could therefore be extra susceptible to this disease. They prefer a higher pH and some general hardness (minerals like calcium and magnesium) in their water to thrive. Algae eating species, like mollies, that are fed a high protein or meat-based food are unlikely to be in optimal health. Feeding old flakes or pellets that haven’t been kept cool, dry, and airtight will compromise nutrition as the fats can oxidize and turn rancid, and important vitamins to a healthy immune response, such as vitamin C, can degrade. Keep wet fingers out of food jars and definitely don’t store the food on top of a hot aquarium light. Buy only the amount of food your fish can consume in a reasonable time. Don’t buy 5 years of fish food at once, even if it’s cheaper.

Consider adding high quality frozen foods to the diet where appropriate, or live foods for species that prefer those. Learn as much as you can about the species’ requirements and do your best to provide those. Overcrowding, as Nora mentioned, is problematic for water quality and bacterial growth, but it can also be problematic for some species behaviorally. If you have fish constantly being intimidated with nowhere to hide, those fish are going to be more stressed and more susceptible to disease. If you have fish that feel safest in a school or shoal, like rasboras or certain tetras, don’t keep only one or two—that will contribute to their stress. If you’ve got fish who naturally sift sand, don’t keep them with large gravel or on a bare bottom (with the exception of short-term quarantine or treatment). Give them the sand they want. Fish that want a dark hiding spot, like plecos, won’t thrive without that security. The art and science of fishkeeping is understanding all these different factors and balancing how you can best provide them. Besides—this is the fun stuff! Understanding and attempting to provide for these needs for our fish is a big part of what we love about this incredible hobby.

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to Dr. Kevin Snekvik, the veterinary pathologist who evaluated the fish mentioned in this article.

Reputable Resources:

CDC Resource about zoonotic diseases people can get from fish.

Francis-Floyd, R. Mycobacterial infections of fish. SRAC Publication No. 4706; 2011.

Noga EJ. Fish Disease : Diagnosis and Treatment. Second edition. Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.